- Home

- Michael Cunningham

A Wild Swan Page 5

A Wild Swan Read online

Page 5

“But you’d be married to him. That would be the man who was going to kill you if you didn’t produce the goods.”

She lifts her head and looks at you.

“My father could live in the palace with me.”

“And yet. You can’t marry a monster.”

“My father would live in the castle. The king’s physicians would attend to him. He’s ill, grain dust gets into your lungs.”

You’re as surprised as she is when you hear yourself say, “Promise me your firstborn child, then.”

She merely blinks in astonishment, by way of an answer.

You’ve said it, though. You might as well forge on.

“Let me raise your first child,” you say. “I’ll be a good father, I’ll teach the child magic, I’ll teach the child generosity and forgiveness. The king isn’t going to be much along those lines, don’t you think?”

“If I refuse,” she says, “will you expose me?”

Oh.

You don’t want to descend to blackmail. You wish she hadn’t posed the question, and you have no idea about how to answer. You’d never expose her. But you’re so sure about your ability to rescue the still-unconceived child, who will, without your help, be abused by the father (don’t men who’ve been abused always do the same to their children?), who’ll become another punishing and capricious king in his own time, who’ll demand meaningless parades and still-gaudier towers and who knows what else.

She interprets your silence as a yes. Yes, you’ll turn her in if she doesn’t promise the child to you.

She says, “All right, then. I promise to give you my firstborn child.”

You could take it back. You could tell her you were kidding, you’d never take a woman’s child.

But you find—surprise—that you like this capitulation from her, this helpless acceding, from the most recent embodiment of all the girls over all the years who’ve given you nothing, not even a curious glance.

Welcome to the darker side of love.

You leave again without speaking. This time, though, it’s not from fear of embarrassment. This time it’s because you’re greedy and ashamed, it’s because you want the child, you need the child, and yet you can’t bear to be yourself at this moment; you can’t stand there any longer, enjoying your mastery over her.

* * *

The royal wedding takes place. Suddenly this common girl, this miller’s daughter, is a celebrity; suddenly her face emblazons everything from banners to souvenir coffee mugs.

And she looks like a queen. Her glowy pallor, her dark intelligent eyes, are every bit as royal-looking as they need to be.

A year later, when the little boy is born, you go to the palace.

You’ve thought of letting it pass—of course you have—but after those nights of sleepless wondering over the life ahead, the return to the amplified solitude and hopelessness in which you’ve lived for the past year (people have tried to sell you key chains and medallions with the girl’s face on them, assuming, as well they might, that you’re just another customer; you, who wear the string of garnets under your shirts, who wear the silver ring on your finger) …

You can’t let it pass after the bouts of self-torture about the confines of your face and body. Until those nights of spinning, no girl has ever let you get close enough for you to realize that you’re possessed of wit and allure and compassion, that you’d be coveted, you’d be sought-after, if you were just …

Neither Aunt Farfalee nor the oldest and most revered of the texts has anything to say about transforming gnomes into straight-spined, striking men. Aunt Farfalee told you, in the low, rattling sigh that was once her voice, that magic has its limits; that the flesh has proven consistently, over centuries, vulnerable to afflictions but never, not even for the most potent of wizards, subject to improvement.

You go to the palace.

It’s not hard to get an audience with the king and queen. One of the traditions, a custom so old and entrenched that even this king dare not abolish it, is the weekly Wednesday audience, at which any citizen who wishes to can appear in the throne room and register a complaint, after the king has taken a wife.

You are not the first in line. You wait as a corpulent young woman reports that a coven of witches in her district is causing the goats to walk on their hind legs, and saunter inside as if they owned the place. You wait as an old man objects to the new tax being levied on every denizen who lives past the age of eighty, which is the king’s way of claiming as his own that which would otherwise be passed along to his subjects’ heirs.

As you stand in line, you see that the queen sees you.

She looks entirely natural on the throne, every bit as much as does her image on banners and mugs and key chains. She’s noticed you, but nothing changes in her expression. She listens with the customary feigned attention to the woman whose goats are sitting down to dinner with the family, to the man who doesn’t want his fortune sucked away before he dies. It’s widely known that these audiences with king and queen never produce results of any kind. Still, people want to come and be heard.

As you wait, you notice the girl’s father, the miller (the former miller), seated among the members of court, in a three-cornered hat and ermine collar. He regards the line of assembled supplicants with a dowager aunt’s indignity; with an expression of superiority and sentimental piety—the recently bankrupt man who gambled with his daughter’s life, and happens, thanks to you, to have won.

When your turn arrives, you bow to queen and king. The king nods his traditional, absentminded acknowledgment. His head might have been carved from marble. His eyes are ice-blue under the rim of his gem-encrusted crown. He might already be, in life, the stone version that will top his sarcophagus.

You say, “My queen, I think you know what I’ve come for.”

The king looks disapprovingly at his wife. His face bears no hint of question. He skips over the possibility of innocence. He only wonders what, exactly, it is she must have done.

The queen nods. You can’t tell what’s going through her mind. She’s learned, apparently, during the past year, how to evince an expression of royal opacity, which she did not possess when you were spinning the straw into gold for her.

She says, “Please reconsider.”

You’re not about to reconsider. You might have considered reconsidering before you found yourself in the presence of these two, this tyrannical and ignorant monarch and the girl who agreed to marry him.

You tell her that a promise was made. You leave it at that. She glances over at the king, and can’t conceal a moment of miller’s-daughter nervousness.

She turns to you again. She says, “This is awkward, isn’t it?”

You waver. You’re assaulted by conflicting emotions. You understand the position she’s in. You care for her. You’re in love with her. It’s probably the hopeless ferocity of your love that impels you to stand firm, to refuse her refusal—she who has on one hand succeeded spectacularly and, on the other, consented to what has to be, at best, a cold and brutal marriage. You can’t simply relent and walk back out of the room. You can’t bring yourself to be so debased.

She doesn’t care for you, after all. You’re someone who did her a favor, once. She doesn’t even know your name.

With that thought, you decide to offer a compromise.

You tell her she has three days to guess your name, in the general spirit of her husband’s fixation on threes. If she can accomplish that, if she can guess your name within the next three days, the deal’s off.

If she can’t …

You do not of course say this aloud, but if she can’t, you’ll raise the child in a forest glade. You’ll teach him the botanical names of the trees, and the secret names of the animals. You’ll instruct him in the arts of mercy and patience. And you’ll see, in the boy, certain of her aspects—the great dark pools of her eyes, maybe, or her slightly exaggerated, aristocratic nose.

The queen nods in agreement. The k

ing scowls. He can’t, however, ask questions, not here, not with his subjects lined up before him. He can’t appear to be baffled, underinformed, misused.

You bow again and, as straight-backed as your torqued spine will allow it, you back out of the throne room.

* * *

You’ll never know what went on between queen and king once they were alone together. You hope she confessed everything, and insisted that a vow, once made, can’t be broken. You even go so far as to imagine she might defend you for your offer of a possible reprieve.

You suspect, though, that she still feels endangered; that she can’t be sure her husband will forgive her for allowing him to believe she herself had spun the straw into gold. Having produced a male heir she has now, after all, rendered herself dispensable. And so, when confronted, she probably came up with … some tale of spells and curses, some fabrication in which you, a hobgoblin, are entirely to blame.

You wish you could feel more purely angry about that possibility. You wish you didn’t sympathize, not even a little, with her, in the predicament she’s created for herself.

This, then, is love. This is the experience from which you’ve felt exiled for so long. This rage mixed up with empathy; this simultaneous desire for admiration and victory.

You wish you found it more unpleasant. Or, at any rate, you wish you found it as unpleasant as it actually is.

* * *

The queen sends messengers out all over the kingdom, in an attempt to track down your name. You know how futile that is. You live in a cottage carved into a tree, so deep in the woods that no hiker or wanderer has ever passed by. You have no friends, and your relatives live not only far away but in residences at least as obscure as your own (consider Aunt Farfalee’s tiny grotto, reachable only by swimming fifty feet underwater). You’re not registered anywhere. You’ve never signed anything.

You return to the castle the next day, and the next. The king scowls murderously (what story has he been told?) as the queen runs through a gamut of guesses.

Althalos? Borin? Cassius? Cedric? Destrain? Fendrel? Hadrian? Gavin? Gregory? Lief? Merek? Rowan? Rulf? Sadon? Tybalt? Xalvador? Zane?

No no no no no no no no no no no no no no no no and no.

It’s looking good.

But then, on the night of the second day, you make your fatal mistake. You’ll wonder, afterward—why did I build a fire in front of the cottage tree, and do that little song and dance? It seemed harmless at the time, and you were so happy, so sure. You’d found yourself sitting alone in your parlor, thinking of where the cradle should go, wondering who’d teach you to fold a diaper, picturing the child’s face as he looks up into yours and says, Father.

It’s too much, just sitting inside like that, by yourself. It’s too little. You hurry out into the blackness of the forest night, into the chirruping of the insects and the far-off hoots of the owls. You build a fire. You grant yourself a pint of ale, and then you grant yourself another.

And, almost against your own will, it seems that you’re dancing around the fire. It seems that you’ve made up a song.

Tonight I brew, tomorrow I bake,

And then the queen’s child I will take.

For little knows the royal dame …

How likely is it that the youngest of the queen’s messengers, the one most desperate for advancement, the one who’s been threatened with dismissal (he’s too avid and dramatic in his delivery of messages, he bows too low, he’s getting on the king’s nerves) … how likely is it that that particular young hustler, knowing every inch of the civilized kingdom to have been scoured already, every door knocked on, thought to go out into the woods that night, wondering if he was wasting precious time but hoping that maybe, maybe, the little man lived off the grid …

How likely is it that he sees your fire, creeps through the bracken, and listens to the ditty you’re singing?

* * *

You return, triumphant, to the castle on the third and final afternoon. You are for the first time in your life a figure of power, of threat. Finally, you cannot be ignored or dismissed.

The queen appears to be flustered. She says, “Well, then, this is my last chance.”

You have the courtesy to refrain from answering.

She says, “Is it Brom?”

No.

“Is it Leofrick?”

No.

“Is it Ulric?”

No.

Then there is a moment—a millimoment, the tiniest imaginable fraction of time—when the queen thinks of giving her baby to you. You see it on her face. There’s a moment when she knows she could rescue you as you once rescued her; when she imagines throwing it all away and going off with you and her child. She does not, could not, love you, but she remembers standing in the room on that first night, when the straw started turning to gold; when she understood that an impossible situation had been met with an impossible result; when she thoughtlessly laid her hand on the sackcloth-covered gnarls of your shoulder … She thinks (whoosh, by the time you’ve read whoosh, she’s no longer thinking of it) that she could leave her heartless husband, she could live in the woods with you and the child …

Whoosh.

The king shoots her an arctic glare. She looks at you, her dark eyes avid and level, her neck arched and her shoulders flung back.

She speaks your name.

It’s not possible.

The king grins a conquering, predatory grin. The queen turns away.

The world, which had been about to transform itself, changes back again. The world reveals itself to be nothing more than you, scuttling out of the throne room, hurrying through town, returning to the empty little house that’s always there, that’s always been there, waiting for you.

You stamp your right foot. You stamp it so hard, with such enchantment-compelled force, that it goes right through the marble floor, sinks to your ankle.

You stamp your left foot. Same thing. You are standing now, trembling, insane with fury and disappointment, ankle-deep in the royal floor.

The queen keeps her face averted. The king emits a peal of laughter that sounds like disdain itself.

And with that, you split in half.

It’s the strangest imaginable sensation. It’s as if some strip of invisible tape that’s been holding you together, from mid-forehead to crotch, has suddenly been stripped away. It’s no more painful than pulling off a bandage. And then you fall onto your knees, and you’re looking at yourself, twice, both of you pitched forward, blinking in astonishment at a self who is blinking in astonishment at you, who are blinking in astonishment at him, who is blinking in astonishment at you …

The queen silently summons two of the guards, who lift you in two pieces from the floor in which you’ve become mired, who carry you, one half apiece, out of the room. They take you all the way back to your place in the woods, and leave you there.

There are two of you now. Neither is sufficient unto itself, but you learn, over time, to join your two halves together, and hobble around. There are limits to what you can do, though you’re able to get from place to place. Each half, naturally enough, requires the cooperation of the other, and you find yourself getting snappish with yourself; you find yourself cursing yourself for your clumsiness, your overeagerness, your lack of consideration for your other half. You feel it doubly. Still, you go on. Still, you step in tandem, make your slow and careful way up and down the stairs, admonishing, warning, each of you urging the other to slow down, or speed up, or wait a second. What else can you do? Each would be helpless without the other. Each would be stranded, laid flat, abandoned, bereft.

STEADFAST; TIN

It’s his lucky night. She’s relented, after two years of aloof and chilly friendliness. Finally, cherries have appeared in all three of his slot machine windows. At the kegger thrown by his fraternity (it’s spring by the calendar, but wind still knifes in off the lake, the grass is still sere), she’s gotten a little drunker than she’d intended to, because she’s ju

st been abandoned by a boy she’d thought she might love; a boy who, when he left, took with him her first ideas about a cogent and convincing future.

At the frat party, her best friend whispers to her, Go with that guy, give both of you a break, haven’t you already observed your second anniversary of him mooning over you? And hey, the friend whispers, he’s just hot enough and just dumb enough for tonight, which, honestly sweetheart, you could use right now, it’s part of your recovery program, it’s your post-asshole-boyfriend vacation, just take the poor fuck for a spin, it’ll make you feel better, you need a little, how to put it, unintensity.

He’s drawn to remote girls, unavailable girls, girls who don’t fall for it, being, as he is, a boy who might have been carved by Michelangelo; one of those exceptional beings who wear their beauty as if it were a common human state, and not an aberration. A remote and unavailable girl is rare for him.

Upstairs, in his room, he’s got her shirt unbuttoned, he’s fingering her crotch, which is pleasant for her, but only pleasant. She’s been right, since he first locked eyes with her in Humanities 101—these hunky, uber-confident guys are never truly adept, they’ve never had to be, they’ve received their educations at the hands of girls who were too grateful, too enamored; girls who failed to teach them properly. This rough groping, these inexpert kisses, have been enough for those simple and besotted girls whose main objective was to keep him coming around. He must have had sex with a hundred girls, more than a hundred, and every one of them, it seems, has done little more than cooperate; than assure him that he’s been right all along about what a girl wants, what a girl needs.

She’s not that patient. She’s not that interested.

So she steps back out of his embrace and strips, with the quick mechanical carelessness of a teammate in the locker room.

Oh. Well. Wow. This is a new one on him, this matter-of-fact, let’s-get-on-with-it attitude.

It means he hasn’t had time to prepare her, to slip her the abashed confession that’s worked every other time, since he started college.

Disconcerted, confused, he strips as well. He can’t think of anything else to do.

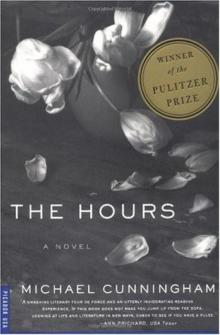

The Hours

The Hours Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown

Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown Golden States

Golden States A Wild Swan

A Wild Swan A Home at the End of the World

A Home at the End of the World Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood Specimen Days

Specimen Days Land's End

Land's End By Nightfall

By Nightfall Hours

Hours