- Home

- Michael Cunningham

Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood Read online

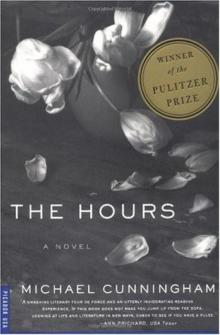

Michael Cunningham is the author of the bestselling novel The Hours, which won both the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award and was adapted into an Academy Award-winning film; A Home at the End of the World, also adapted for the screen; and Specimen Days. Most recently, he edited Laws for Creations, a collection of poetry and prose by Walt Whitman. He lives in New York.

ALSO BY

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

A Home at the End of the World

The Hours

Specimen Days

Laws for Creations (ed.)

Additional Praise for Flesh and Blood

“Flesh and Blood is the real thing—a novel about an American family surviving an American half-century that manages to be terrifically engaging and delicately written and heartfelt at the same time.”

—Bruce Barcott, Seattle Weekly

“Stunning . . . In precise and beautiful prose, he explores the desire for connection and the knowledge that most of the time we remain adrift.”

—US magazine

“Reading Michael Cunningham is like putting on see-through glasses. He’s got this way of exposing his characters’ deepest inclinations and motivations, letting us peer through glass directly into their souls.”

—Matthew Gilbert, The Boston Globe

“Masterful. . . Crosses emotional and sexual boundaries with rare humanity and art.”

—Mirahella

“Call Flesh and Blood a soap opera for people who value intelligent and subtle writing. . . . The telling has such grace and style that even the most predictable event catches one off guard. This is a superior novel.”

—Ronald Reed, Fort Worth Star-Telegram

‘Without ever glossing over the often irreparable harm people do to those they love, this thoughtful novel reminds us that in the end, the love is more important than the harm.”

—Wendy Smith, The Plain Dealer (Cleveland)

“Voluptuous . . . this elegiac meditation on anger, mistrust, and loneliness has a ferocious perceptiveness that puts Cunningham on another level as an artist.”

—Dwight Garner, Harpers Bazaar

“Flesh and Blood is nothing short of literary genius.”

—Owen Keehnen, Men’s Style

“The story of Constantine Stassos freshly examines the American immigrant experience and conflict between generations. . . . Thoroughly realized action, vivid character delineation, and the splendid control of language guarantee both the unity and powerful impact of this successful novel.”

—Library Journal

FLESH

AND

BLOOD

FLESH

AND

BLOOD

MICHAEL

CUNNINGHAM

Picador

Farrar, Straus and Giroux / New York

FLESH AND BLOOD. Copyright © 1995 by Michael Cunningham. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. For information, address Picador, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

www.picadorusa.com

Picador® is a U.S. registered trademark and is used by Farrar, Straus and Giroux under license from Pan Books Limited.

For information on Picador Reading Group Guides, as well as ordering, please contact Picador.

Phone: 646-307-5629

Fax: 212-253-9627

E-mail: [email protected]

“It’s Not Unusual”; words and music by Gordon Mills and Les Reed © Copyright 1965 Leeds Music, Ltd. All rights for USA and Canada controlled and administered by Duchess Music Corporation, an MCA Company. All rights reserved. Used by permission. International copyright secured.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cunningham, Michael, 1952-

Flesh and blood / Michael Cunningham.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-312-42668-2

ISBN-10: 0-312-42668-2

I. Title.

- PS3553.U484 F57 1995

813’.54—dc20

94024628

First published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

THIS BOOK IS FOR

DONNA LEE &

CRISTINA THORSON

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

I Car Ballet

II Criminal Wisdom

III Inside The Music

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I’d like to thank Joel Conarroe, Ken Corbett, Stacey D’Erasmo, Stephen Kory Friedman, Jonathan Galassi, Gail Hochman, and Anne Rumsey, all of whom read this book in various stages. Also enormously helpful were Evelyn Burkhalter, Marcelle Clements, Dorian Corey, Anne D’Adesky, Paul Elie, Nick Flynn, William Forlenza, Dennis Geiger, Nick Humy, Adam Moss, Angie Xtravaganza, and the members of the House of Xtravaganza, particularly Danny and Hector. The John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation provided deeply appreciated financial support, and on an unseasonably cold morning in Washington Square Park, Larry Kramer generously provided me with the title.

Once an angry man dragged his father along the ground through his own orchard. “Stop!” cried the groaning old man at last. “Stop! I did not drag my father beyond this tree”

—GERTRUDE STEIN, The Making of Americans

I

CAR

BALLET

1935/ Constantine, eight years old, was working in his father’s garden and thinking about his own garden, a square of powdered granite he had staked out and combed into rows at the top of his family’s land. First he weeded his father’s bean rows and then he crawled among the gnarls and snags of his father’s vineyard, tying errant tendrils back to the stakes with rough brown cord that was to his mind the exact color and texture of righteous, doomed effort. When his father talked about “working ourselves to death to keep ourselves alive,” Constantine imagined this cord, coarse and strong and drab, electric with stray hairs of its own, wrapping the world up into an awkward parcel that would not submit or stay tied, just as the grapevines kept working themselves loose and shooting out at ecstatic, skyward angles. It was one of his jobs to train the vines, and he had come to despise and respect them for their wild insistence. The vines had a secret, tangled life, a slumbering will, but it was he, Constantine, who would suffer if they weren’t kept staked and orderly. His father had a merciless eye that could find one bad straw in ten bales of good intentions.

As he worked he thought of his garden, hidden away in the blare of the hilltop sun, three square feet so useless to his father’s tightly bound future that they were given over as a toy to Constantine, the youngest. The earth in his garden was little more than a quarter inch of dust caught in a declivity of rock, but he would draw fruit from it by determination and work, the push of his own will. From his mother’s kitchen he had spirited dozens of seeds, the odd ones that stuck to the knife or fell on the floor no matter how carefully she checked herself for the sin of waste. His garden lay high on a crown of scorched rock where no one bothered to go; if it produced he could tend the crop without telling anyone. He could wait until harvest time and descend triumphantly, carrying an eggplant or a pepper, perhaps a tomato. He could walk through the autumn dusk to the house where his mother would be laying out supper for his father and brothers. The light would be at his back, hammered and golden. It would cut into the dimness of the kitchen as he threw open the door. His mother and father and brothers would look at him, the runt, of whom so little was expected. When he stood in the vineyard looking down at the world—the ruins of the Papandreous’ farm, the Kalamata Company’s olive groves, the remote shimmer of town—he thought of climbing the rocks one day to find green shoots pushing through his patch of dust. The priest counseled that miracles were the result of diligence and blind faith. He was faithful.<

br />

And he was diligent. Every day he took his ration of water, drank half, and sprinkled half over his seeds. That was easy, but he needed better soil as well. The pants sewn by his mother had no pockets, and it would be impossible to steal handfuls of dirt from his father’s garden and climb with them past the goats’ shed and across the curving face of the rock without being detected. So he stole the only way he could, by bending over every evening at the end of the workday, as if tying down one last low vine, and filling his mouth with earth. The soil had a heady, fecal taste; a darkness on his tongue that was at once revolting and strangely, dangerously delicious. With his mouth full he made his way up the steep yard to the rocks. There was not much risk, even if he passed his father or one of his brothers. They were used to him not speaking. They believed he was silent because his thoughts were simple. In fact, he kept quiet because he feared mistakes/The world was made of mistakes, a thorny tangle, and no amount of cord, however fastidiously tied, could bind them all down. Punishment waited everywhere. It was wiser not to speak. Every evening he walked in his customary silence past whatever brothers might still be at work among the goats, holding his cheeks in so no one would guess his mouth was full. As he crossed the yard and ascended the rocks he struggled not to swallow but inevitably he did, and some of the dirt sifted down his throat, reinfecting him with its pungent black taste. The dirt was threaded with goat dung, and his eyes watered. Still, by the time he reached the top, there remained a fair-sized ball of wet earth to spit into his palm. Quickly then, fearful that one of his brothers might have followed to tease him, he worked the handful of soil into his miniature garden. It was drenched with his saliva. He massaged it in and thought of his mother, who forgot to look at him because her own life held too many troubles for her to watch. He thought of her carrying food to his ravenous, shouting brothers. He thought of how her face would look as he came through the door one harvest evening. He would stand in the bent, dusty light before his surprised family. Then he would walk up to the table and lay out what he’d brought: a pepper, an eggplant, a tomato.

1949/ “It’s some kind of night, isn’t it?” Mary said. Constantine couldn’t answer. Her courage and beauty, the pale straight-spined fact of her, caught in his throat. He sat on her parents’ swing, which creaked, and watched helplessly as she leaned over the porch railing. Her skirt whisked against her legs. The dark New Jersey wind played in her hair.

“Oh, nights like this really get to me,” she said. “Will you look at all those stars? I’d like to scoop up big handfuls and sprinkle them over your head.”

“Mm,” Constantine said, a muffled groan he hoped had signified his pleasure. It was almost six months now, and he still couldn’t trust his fortune. He couldn’t believe he was dating this magnificent American girl. He had a second life now, inside her head. He worried, almost every moment, that she would realize her mistake.

“You’d look wonderful with stars all over you,” she said, but he could tell from her voice that she’d grown tired of her own idea. When her voice dropped and her hands went idly to her hair she’d lost interest in whatever she was saying, although she could keep talking without listening to herself. He’d never known anyone so steadfast and yet so easily bored.

To bring her back he stood up and went to the railing. He looked with her at her parents’ small back yard, her father’s toolshed, the riot of stars. “You are the one that looks wonderful,” he whispered.

“Oh, I’m all right,” she said, without turning to him. Her voice maintained its hazy, sleepwalker’s quality. “But you’re the beauty, and you know it’s true. Just the other day a girl at school was asking if it didn’t make me nervous, to be seeing a fellow as good-looking as you. She was speaking out in favor of homely boys.”

“I am a homely boy,” he said.

Now she did turn to face him. He was surprised to see an angry flush on her cheeks.

“Don’t fish,” she said. “It’s unbecoming in a man.”

Again, he’d said the wrong thing. He’d thought that by ‘homely’ she’d meant boys who cared about making a home. Always, he tried to position himself so that he resembled what she wanted most.

“I don’t—” he said. “I only mean—”

She nodded, and ran her finger down his shirtfront. “Don’t mind me,” she said. “I’m a little jumpy tonight, for some reason. All these stars seem to be driving me just slightly crazy.”

“Yes,” he said. “They are very beautiful.”

She took her finger from his shirt. She turned back to the yard, and began twisting a strand of hair around her finger. Constantine stared at her finger with a wistful desire that lodged in his gullet like a stone.

“But they’re wasting themselves over Newark,” she said. “Look at them, shining away for all they’re worth. It’s sad, don’t you think?”

Constantine was in love with Newark. He loved the proud thrust of smokestacks, the simple domestic serenity of square brick houses. Still, he knew Mary needed him to disdain all the ordinary beauties her presence had helped teach him to adore.

“Sad,” he said. “Yes, it’s very sad.”

“Oh, Con, I’m tired of, I don’t know. Everything.”

“You are tired of everything?” he said.

She laughed, and her laughter had a mocking edge. Sometimes he said things that were humorous to her in ways he couldn’t follow. Direct statements or questions of his often seemed to confirm some bitter joke known only to her.

“Well, I’m tired of school. I don’t see the use of all this history and geometry. I want to get a job, like you.”

“You want to work a construction crew?” he said.

“No, silly. I could work in an office, though. Or a dress shop.”

“You should finish school.”

“I can’t think what for. I’m no good at it.”

“You are good,” he said. “You are good at everything you do.”

She wrapped the hair tightly around her finger. She was angry again. How was it possible to know? Sometimes flattery was wanted. Sometimes flattery was hurled back like a handful of gravel.

“I know you think I’m perfect,” she said in a low voice. “Well, I’m not. You and my father both need to realize that.”

“I know you are not perfect,” he said, and his voice sounded wrong. It was hollow and young, with an apologetic squeak. In a deeper voice he added, “You are the girl I love.” Was a statement like that part of the immense, unguessable joke?

She didn’t laugh. “We both say that.” She continued looking deep into the yard. “Love love love. Con, how do you know you love me?”

“I know love,” he said. “I think about you. Everything I do is for you.”

“How would it make you feel if I told you I sometimes forget about you for whole hours?”

He didn’t speak. A small animal, a cat or an opossum, browsed quietly among the garbage cans.

“It’s not that I don’t care about you,” she said. “I do, I care about you awfully. Maybe I’m just shallow. But I keep wondering if love isn’t supposed to change everything. I mean, I’m still myself. I still wake up in the mornings and, well, there I am, about to live another day.”

Constantine’s ears had filled with an echoing, oceanic sound. Was this the moment? Was she going to tell him it would be better if they didn’t see each other for a while? To stop time, to fill the air, he said, “I can take you anyplace. I am assistant foreman, soon I’ll know enough to get other jobs.”

She looked at him. Her face was clear.

“I want to have a better life,” she said. “I’m not so awfully greedy, really I’m not, I just—”

Her attention drifted from his face to the porch on which they stood. Constantine saw the porch through Mary’s eyes. A rusty swing, a carton of milk bottles, a wan geranium growing in a small ceramic pot. He was aware of her parents and her brothers moving around inside the house, each nursing a private bouquet of complaints. Her fathe

r was poisoned by factory dust. Her mother lived among the ruins of a beauty she must once have thought would carry her into the next life. Her lazy brother Joey sought the bottom of everything with blind instincts, the way a catfish sought the bottom of a river.

Constantine took Mary’s small hand, squeezed it in his. “You will,” he said. “Yes. Everything you want can happen.”

“Do you honestly think so?”

“Yes. Yes, I know it.”

She closed her eyes. They were safe, at that moment, from the joke, and he knew that it was possible to kiss her.

1958/ Mary was assembling a rabbit-shaped Easter cake according to the instructions in a magazine, cutting ears and a tail from a layer of yellow cake round and placidly innocent as a nursery moon. She worked in a transport of concentration. Her eyes were dark with their focus, and the tip of her tongue protruded from between her lips. She sliced out one perfect ear and was starting on the next when Zoe, her youngest, bumped against her ankle. Mary gasped, and cut a nick big as a man’s thumbnail into the second ear.

“Darn,” she whispered. Before Zoe bumped into her, Mary had been wholly usurped by the need to cut a flawless, symmetrical ear out of a freshly baked cake. She had been no one and nothing else.

She looked at Zoe, who was crouched at her feet, whimpering and slapping the speckled linoleum with the palms of her hands. Mary knew what was coming. Soon Zoe would topple over into a fit of dissatisfaction from which no comfort would rouse her. Zoe was the strangest of the children, a locked box Mary couldn’t penetrate with kindness or impatience or little gifts of food. Susan and Billy were more comprehensible; they cried when they were hungry or tired. They’d look beseechingly at Mary, even in their worst tantrums, as if to say, Give me anything, any little reason to feel whole again. A toy could console them, or a cookie. But Zoe seemed to welcome misery. She could fuss for an hour or longer for no discernible reason—she was preparing to do so now. Mary could feel it coming, the way her own mother had claimed to feel the approach of rain on a fair day. She felt it in her joints. Spread before her on the countertop were cake layers, coconut icing, gumdrops, and licorice whips. She looked at her work and she looked down at the furious child who was about to fall into despair with a kind of voluptuous and hopeless pleasure, the way a grown woman might fall into bed after still another frustrating day.

The Hours

The Hours Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown

Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown Golden States

Golden States A Wild Swan

A Wild Swan A Home at the End of the World

A Home at the End of the World Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood Specimen Days

Specimen Days Land's End

Land's End By Nightfall

By Nightfall Hours

Hours