- Home

- Michael Cunningham

By Nightfall Page 3

By Nightfall Read online

Page 3

THE BRONZE AGE

The bedroom is full of the gray semilight particular to New York, an effusion, seemingly sourceless; a steady shadowless illumination that might just as well be emanating up from the streets as falling down from the sky. Peter and Rebecca are in bed with coffee and the Times.

They do not lie close to each other. Rebecca is absorbed in the book review. Here she is, grown from a tough, wise girl to a savvy and rather cool-hearted woman, weary of reassuring Peter about, well, almost everything; grown to be a severe if affectionate critic. Here is her no-nonsense girlhood transmogrified into a womanly capacity for icy, calmly delivered judgments.

Peter’s BlackBerry pipes out its soft, flutey tone. He and Rebecca trade looks—who’d call on a Sunday morning?

“Hello.”

“Peter? It’s Bette. I hope I’m not calling too early.”

“No, we’re up.”

He glances at Rebecca, mouths the word “Bette.”

“You okay?” he asks.

“I’m okay. Are you by any remote chance free for lunch today?”

A second glance at Rebecca. Sunday is supposed to be their day together.

“Uh, yeah,” he says. “I think so.”

“I can come downtown.”

“Okay. Sure. What, like, one-ish?”

“One-ish is good.”

“Where would you like to go?”

“I can never think of a place.”

“Me neither.”

“Doesn’t it always seem like there’s some perfect, obvious restaurant and you just can’t think of it?” she says.

“Plus, on a Sunday, there’s a lot of places we won’t be able to get into. Like Prune. Or the Little Owl. I mean, we could try.”

“It’s my fault. Who calls to make a lunch date at the last minute on a Sunday?”

“You want to tell me what’s up?”

“I’d rather tell you in person.”

“What if I come uptown?”

“I’d never ask you to do that.”

“I’ve been wanting to see the Hirst at the Met.”

“Me, too. But really, how could I live with myself if I not only call you on your day off, but make you schlep uptown, too?”

“I’ve done more for people I care less about.”

“Payard’s will be packed. I could probably get us a table at JoJo. It’s not as, you know. Brunchy up here.”

“Fine.”

“Do you mind JoJo? The food’s good, and there’s nothing really close to the Met…”

“JoJo’s okay.”

“You, Peter Harris, are a mensch.”

“So true.”

“I’ll call. If they can’t take us at one, I’ll call you back.”

“Okay. Great.”

He clicks off, wipes a smudge from the face of his BlackBerry on the edge of the sheet.

“That was Bette,” he says.

Is it a betrayal, making a lunch date on a Sunday? It would help if he knew how serious Bette’s… situation is.

“Did she say what it is?” Rebecca asks.

“She wants to have lunch.”

“But she didn’t say.”

“No.”

They both hesitate. Of course, it can’t be good. Bette is in her midsixties. Her mother died of breast cancer, what, ten or so years ago.

Rebecca says, “You know, if we say, I hope it’s not cancer, that won’t affect anything one way or the other.”

“You’re right.”

At this moment, he adores her. The cloudy ambivalence burns away. Look at her: the strong-jawed, sensible, slightly archaic lines of her face (her profile could be on a coin)—behind it, how many generations of pale Irish beauties married to wealthy, stolid men?—the graying tumble of her dark hair.

He says, “I wonder why she called me.”

“You’re her friend.”

“But we’re not friend friends.”

“Maybe she wants to practice. You know, try telling somebody she’s not that close to.”

“We don’t know it’s that. Maybe… she wants to confess her love for me.”

“Do you think she’d call you at home about that?”

“I’d say cell phones have made that a moot question.”

“Do you really think?”

“Of course not.”

“Elena’s in love with you.”

“Then I wish she’d fucking buy something.”

“Are you meeting Bette uptown?”

“Yeah. JoJo.”

“Mm.”

“We can go to the Met after, and see the Hirst. I keep wondering how it looks in there.”

“Bette. What is she, sixty-five?”

“Thereabouts. When did you get checked last?”

“I don’t have breast cancer.”

“Don’t say that.”

“It really and truly doesn’t make any difference if you say it or you don’t.”

“I know. But still.”

“If I die, I give you permission to remarry. After a suitable period of mourning.”

“Ditto.”

“Ditto?”

They both laugh.

He says, “Matthew left such elaborate instructions. We knew about the music, we knew about the flowers. We knew which suit to put him in.”

“He didn’t trust your parents and his nineteen-year-old straight brother. Can you blame him?”

“He didn’t even trust Dan.”

“Oh, I bet he trusted Dan. He just wanted to make the decisions himself. Why wouldn’t he?”

Peter nods. Dan Weissman. Twenty-one-year-old boy from Yonkers, working as a waiter, saving to go to Europe for a few months, thinking he’d finish up at NYU when he got back. He believed, he must have believed, at least briefly, that the world was showering bounty on him. He was making good money at the new café-of-the-moment. He and Matthew Harris, his improbably fabulous new boyfriend, would walk together through Berlin and Amsterdam. Madonna had left him fifty-seven dollars on a forty-three-dollar check.

Rebecca says, “I think I want Schubert.”

“Hm?”

“At the memorial. Cremation. Schubert. And please, everybody get drunk afterward. A little Schubert, a little sorrow, and then have drinks and tell funny stories about me.”

“Which Schubert?”

“I don’t know.”

“I think maybe Coltrane for me. Would that be pretentious?”

“No more than Schubert. Do you think Schubert is too pretentious?”

“It’s a funeral. We’re allowed.”

“Maybe Bette’s okay,” she says.

“Maybe. Who knows?”

“Shouldn’t you get in the shower?”

Is she eager for him to go?

He says, “You sure you don’t mind?”

“No, it’s fine. Bette wouldn’t call at the last minute like this if it wasn’t something important.”

Right. Of course. And yet. Sunday really is their day, their only day, shouldn’t she be a little more conflicted about releasing him, no matter how noble the cause?

He glances at the bedside clock, its beautiful aqua numerals. “Shower in twenty minutes,” he says.

And so. Twenty minutes in bed with your wife, reading the Sunday paper: this little cup of time. Black holes are expanding; a section of Arctic ice bigger than Connecticut has just melted away; someone in Darfur who wants desperately to live, who’d let himself believe he’d be one of the survivors, has just been cut open by a machete and for an instant sees his own viscera, the wet red of it darker than he’d imagined. Amid all that, Peter can probably rely on twenty minutes of simple domestic comfort.

Bette Rice has beamed something into the room, though. Call it mortal urgency.

Who ever expected heroism from little Dan Weissman, handsome in his avid-eyed, narrow-faced way, something of the antelope about him; no extravagant passions; Dan who was so clearly meant to be one of the boys Matthew used to date?… Who could poss

ibly have imagined him learning more than some of the doctors knew, facing down the most terrifying nurses, staying with Matthew when he was home and getting him into the protocol they said was closed and being at the hospital those last days and… ? Yes, the list goes on… and no, Dan didn’t mention his own first symptoms until after Matthew was gone. Who expected Matthew and this more or less random boy to become Tristan and fucking Isolde?

You could panic in the face of it all—your brother dead at twenty-two (he’d be forty-seven now), along with his erstwhile boyfriend and every other friend he’d had; slaughters in other countries that might give pause to Attila the Hun; children killing their teachers with guns their fathers left lying around; and by the way, do you think it’ll be another building next time, or will it be a subway or a bridge?

“Have you got the Metro?” he asks Rebecca.

She hands the section over to him, returns to the book review.

“The Martin Puryear is closing in three weeks,” she says. “Please kick me if I miss it.”

“Mm.”

He has twenty minutes. Nineteen, now. He is impossibly fortunate; frighteningly fortunate. Your troubles, little man? Think of them as an appetizer that didn’t turn out quite right. You should sing and frolic, you should make obeisance to any god you can think of, because no one has put a tire over your shoulders and set it on fire, at least not today.

Rebecca says, “Should we call Bea before you go?”

What kind of father would want to put off calling his daughter?

No one has hacked you to death with a machete. But still.

“Let’s call her when I get back,” he says.

“Okay.”

Hard to deny it: Rebecca is just as happy to have a few hours at home without him. One of those long-marriage things, right? You want to be home alone sometimes.

It’s a warm April afternoon suffused with bright gray glow. Peter walks the few blocks to the Spring Street IRT. He’s wearing beat-up suede boots and dark blue jeans and a light blue unironed shirt under a pewter-colored leather jacket. You try not to look too calculated but you are in fact meeting someone at a fancy restaurant uptown and you want—poor fucker—you want to look neither defiantly “downtown” (pathetic, in a man your age) nor like you’ve nicened it up for the dowagers. Peter has gotten better over the years at dressing as the man who’s impersonating the man he actually is. Still, there are days when he can’t shake the feeling that he’s gotten it wrong. And of course it’s grotesque to care about how you look, yet almost impossible not to.

Still, always, there’s the world, which conspires constantly to remind you: no one cares about your boots, pilgrim. There’s Spring Street on this spring day—is it a false spring, though? New York has a habit of squeezing out one last snowfall even after the crocuses are out—the sky so blank you can imagine God forming it with His hands like snowballs and tossing them out, saying, Time, Light, Matter. There’s New York, one of the goddamnedest perturbations ever to ride the shifting surface of the earth. It’s medieval, really, all ramparts and ziggurats and spikes and steeples, entirely possible to see a hunchback cloaked in a Hefty bag stumping along beside a woman carrying a twenty-thousand-dollar purse. And at the same time, overlaid, is a vast nineteenth-century boomtown, raucously alive, eager for the future but nothing rubberized or air-cushioned about it, no hydraulic hush; trains rumbling the pavement, carved limestone women and men—not gods—looking heftily down from cornices as if from a heaven of work and hard-won prosperity, car horns bleating as some citizen in Dockers passes by telling his cell phone “that’s how they’re supposed to be.”

Peter descends the stairs into the roar of an oncoming train.

Bette is already seated when he arrives. Peter follows the hostess through the dark red faux Victoriana of JoJo. When Bette sees Peter she offers a nod and an ironic smile (Bette, a serious person, would wave only if she were drowning). The smile is ironic, Peter suspects, because, well, here they are, at her behest, and sure, the food is good but then there’s the fringe and the little bandy-legged tables. It’s a stage set, it’s whimsical, for God’s sake; but Bette and her husband, Jack, have had their inherited six-room prewar on York and Eighty-fifth forever, he makes a professor’s salary and she makes mid-range art-dealer money and fuck anybody who sneers at her for failing to live downtown in a loft on Mercer Street in a neighborhood where the restaurants are cooler.

When Peter reaches the table, she says, “I can’t believe I’ve dragged you up here.”

Yes, she is in fact irritated with him, for… agreeing to come? For thriving (relatively speaking)?

“It’s fine,” he says, because nothing cleverer comes to mind.

“You’re a kind man. Not a nice man, people tend to get the two mixed up.”

He sits opposite her. Bette Rice: a force. Silver crew cut, austere black-rimmed glasses, Nefertiti profile. She was born to it. Jewish daughter of Brooklyn leftists, may or may not have dated Brian Eno, has a good story about how Rauschenberg gave her her first Diet Coke. When he’s with Bette, Peter can feel like the not-quite-bright high school jock putting moves on the smart, tough girl. Can he help having been born in Milwaukee?

She laser-eyes a waitress, says “Coffee,” doesn’t care that her voice is louder than it needs to be, that a sixtyish Perfect Blonde glances over from the next table.

Peter says, “I hope you’re willing to talk about Elena Petrova’s glasses.”

She holds up a slender hand. One of the three silver rings she wears is taloned, like an obscure torture implement.

“Angel, it’s sweet of you, but I’m not going to put you through the preliminary chitchat. I have breast cancer.”

Did he think that by anticipating it, he’d protected her from it?

“Bette—”

“No, no, they got it.”

“Thank God.”

“What I really want to tell you is, I’m closing the gallery. Right now.”

“Oh.”

Bette offers him a slip of a smile, consoling, maternal even, and he’s reminded that she has two grown sons, neither of whom is particularly screwed up.

Bette says, “They got it this time, and if it comes back, they’ll probably get it next time, too. I’m not dying, not even close to it. But there was a moment. When I first heard what it was, and you know, my mother—”

“I know.”

She gives him a level, sobering look. Don’t be too eager to be good about this, okay?

She says, “I wasn’t so much terrified as I was pissed off. The gallery’s been my whole life for the last forty years, and frankly I’ve been sick of it for the last ten. And now that it’s all going to hell, and everybody’s broke… Anyway. One of my first thoughts was, If this doesn’t kill me, Jack and I are going to change our lives.”

“And so—”

“We’re going to go live in Spain. The boys are fine, we’re going to find a little whitewashed house somewhere and grow tomatoes.”

“You’re kidding.”

She laughs, a dense, throaty sound. She is one of the last living American smokers.

“I know,” she says. “I know. Maybe we’ll be bored out of our minds. Then we’ll sell the goddamned little whitewashed house and go do something else. I just don’t want to do this anymore. Jack is sick of Columbia, too.”

“Blessings on your journey, then.”

The waitress brings Peter’s coffee, asks if they’ve had time to consider the menu, which they haven’t. She says she’ll check back. She is a sweet-faced, sturdy girl with a Georgia accent, somebody’s much-loved daughter, probably newly arrived in New York, determined to sing or act or whatever, extragenial, eager to seem as much like a waitress as she possibly can, not to mention the fact that anyone who can afford to come to a place like JoJo at this moment in history is something of a celebrity by definition.

Bette says, “I want to love art again.”

“I think I know what you mean.”

/> “Who doesn’t? The money thing—”

“I know. And now, all of a sudden, there isn’t any more. Money, I mean.”

“There’s still some.”

“Well, yeah. I mean, I hope that’s true…”

“And it seems we’ve all gone directly from struggling to survive to being semi-established and beside the point.”

Very briefly, an inner careen. We all? Back off, bitch angel of death. I’m not infected by failure.

She says, “I don’t mean you, Peter.”

What must have passed across his face just then?

“Don’t you?”

“I’m being clumsy, aren’t I? I’m beside the point. You’re one of the very few decent, serious people out there. Everyone else is, you know. Either a nineteen-year-old selling his friends’ stuff out of his apartment in Bed-Stuy, or they’re fucking Mobil Oil.”

“Well, yeah. I do know.”

“Aren’t you even a little bit sick of it?”

“Some days,” he says.

“You’re still young.”

“Forty isn’t young.”

Hm, shaved a few years off, didn’t you?

“I haven’t told anyone yet,” she says. “About quitting, I mean. I called you because I thought you might want to take Groff. And maybe one or two of the others. But you like Groff, right?”

Rupert Groff. Not exactly Peter’s thing, but young, and on the cusp. Bette lucked into him two years ago, when she went to give the talk at Yale. Once she’s made the announcement about closing her gallery, he’s the one they’ll all be after.

“I do,” Peter says.

He likes Groff well enough, and really, this is someone who could bring in some serious money.

“I think you’re the best match for him,” Bette says. “I’m afraid one of the giants will snatch him up and ruin him.”

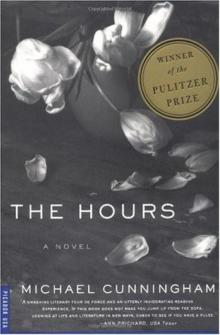

The Hours

The Hours Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown

Land's End: A Walk in Provincetown Golden States

Golden States A Wild Swan

A Wild Swan A Home at the End of the World

A Home at the End of the World Flesh and Blood

Flesh and Blood Specimen Days

Specimen Days Land's End

Land's End By Nightfall

By Nightfall Hours

Hours